“Patience is a lifelong treasure” – a Japanese proverb that nō-men-shi (Noh mask maker) Mitsue Nakamura has embodied and exhibited in her life and her life’s work. Not only because her craft demands it, but because she needed patience in order to forge the unique life that she dreamed of.

Located in Higashiyama, a charming area in historic Kyoto that is now dotted with antique shops brimming with Japanese art, culture and tradition, it is here that you find Ms. Nakamura’s home; a perfect fit for a woman who has been perfecting her craft for over 30 years.

“The house is over one-hundred years old” she says in English with a shy smile.

The cool autumn air mixes with the smell of hinoki wood from which the nō-men (noh masks) are made, adding to the presence of the traditional Japanese home, that also serves as her workshop.

Ms Nakamura’s masks are used by some of Japan’s top Noh (Classical Japanese musical drama) performers to tell intriguing and fascinating tales. Originating in the 14th century, Noh, which comes from the Japanese word for “skill” or “talent”, is Japan’s oldest theater art and is recognized by UNESCO as having “Intangible Cultural Heritage”. One of only 30 professional nō-men-shi in all of Japan, just five of which are women, this masterful creator behind these storytelling tools has her own interesting story.

Born in Mie prefecture in 1947, Ms Nakamura’s family moved to Osaka when she was five years old. She showed a love for art from a young age and started painting portraits as she found herself drawn to human faces. She grew up in a generation of women who were generally expected to get married and raise children right after graduating high school. For those who did find work, it was customary to quit their jobs after marrying and not join the workforce again.

However, Ms Nakamura’s parents did not place so much emphasis on her getting married, and they always encouraged her to pursue her talents. She herself didn’t want to settle down right away, so after graduating high school, she continued to study art.

In 1969 she graduated from Kyoto City University of Fine Arts (presently, Kyoto City University of Arts) and went on to teach high-school art for two years. She said while she enjoyed teaching the students, she didn’t like the staff room politics.

“I wanted to pursue something that would allow me to work on my own, that would allow for more freedom and independence,” she said.

This dream, however, was put on hold for a while when after two years of teaching, she did decide to get married, and had two children. But married life wasn’t what she had hoped it would be, and she soon realized she wanted to leave her husband. Making decisions with her children’s best interests at heart, however, she felt she had to wait until they were over 18 before divorcing.

Her dream of becoming a Noh mask craftswoman began when her kids started going to kindergarten. She had a little more free time during the day, so she decided to spend that time learning how to make Noh masks. It was 1983, she was in her mid-thirties, and this was her first step on what would be a 25-year journey to achieving her dream of earning her own salary through being a professional Noh mask maker and teacher.

In 1990, she began to study with the esteemed Hori Yasuemon, a brilliant mask maker renowned within the Noh community. After only two years under his instruction, she reached a major milestone on her path to success. One particularly well-known Noh actor, noticed and became fascinated with her knack for the art of Noh mask making, and bought the first mask she ever sold.

“I was so shocked, I didn’t know how to respond when he asked me the price,” she said with a laugh. Later, her reputation reached the attention of the head of the Kanze school (one of the five major schools of Noh), Kiyokazu Kanze.

“I’ll never forget how I felt when he offered to buy my mask. I still cannot express how surprised, moved, and joyful I felt.”

Kanze has bought four masks from her over time, four of more than 200 masks she has sold throughout her career.

Each Noh mask is carved from a single piece of hinoki, and takes several weeks to a month to complete. Many become heirlooms and are considered a sacred entity, so it is little surprise they can sell upwards of ¥500,000.

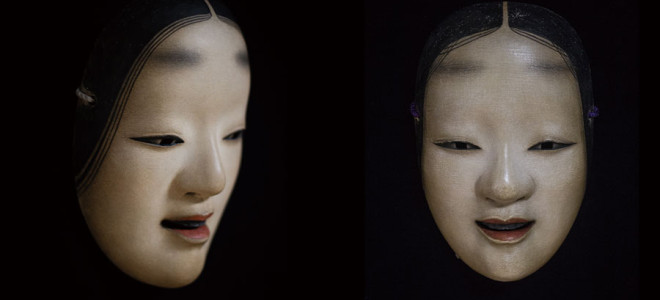

It is the actor’s job to infuse the mask and bring the emotions to the audience with subtle movements of the head. Terasu (tilting upwards) generally gives a lighter feeling of laughter or smiling; kumorasu (tilting downwards) gives a range of sadder expressions, such as frowning or crying.

By using small, controlled movements, a professional Noh actor can have a full range of emotions from one mask.

It is the job of the mask maker to instill a variety of emotions into the mask while also ensuring it remains in a state of neutrality.

![]()

Ms Nakamura says she always has in mind which mask she will create before she begins, but sometimes the wood has its own ideas, and a different character takes over during the carving process. To create vessels of such strong yet subtle expression, a mask maker must put their heart and soul into carving out these characters.

“When creating a mask of a beautiful girl or child I feel very happy but when creating an onryo (vengeful spirit or ghost) I can feel sorrow or anger,” she said.

It may be no coincidence that Ms Nakamura wields a chisel so naturally and with such skill. One of the main chisels used for carving Noh masks is called tou, which is another word meaning samurai sword. Ms Nakamura always credited her parents for encouraging her to learn a skill that could allow her to support herself without a husband, and this modern thinking could be attributed to her family being of samurai lineage. After the reforms of the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912) that saw the ushering in of modern Japan, her ancestors learned the importance of being self sufficient, independent, and having a diverse range of skills – values which were passed down to her.

Samurai believed their souls dwelled in their swords which is why they treasured them. Ms Nakamura’s masks embody many souls when worn on the stage, and her creations are absolute treasures.

Things you should know about Noh

Originally there were around 60 types of Noh masks but today there over 200.

The waka-onna (young woman), is perhaps the most well-known and depicts the standard of classical beauty for medieval Japan. The classic Noh mask, the onnamen (woman mask), has many variations that at first glance might go unnoticed, even when looking at them side-by-side.

The hannya mask with horns represents a distressed demon often used during the transformation of a female character when she reveals her jealousy, anger or sorrow.

Noh masks exaggerate features such as the contours of the mouth and eyes. This leaves the mask with a neutral expression that can take on many different forms when viewed from different angles.

When the actor goes to the kagami no ma (mirror room) to put on the mask, they use the word kakeru (to hang), or tsukeru (to attach), instead of kaburu (putting on clothing), to symbolize that the actor is transforming into that character.