It’s a hot summer’s night in August and Obon (the festival of the dead) is just around the corner. The moon is nestled high in the sky illuminating the guests, all clad in elegant blue robes, as they make their way inside. Immediately they are bathed in an eerie, blue glow emanating from the 100 aoandon (blue lanterns), painting everyone in an otherworldly hue. Their eyes begin to adjust to the shapes and shadows swirling around them as they gather and sit in a circle on the floor.

One by one, guests take turns telling their eerie stories; recounting bizarre, strange and supernatural occurrences; reciting urban legends, myths, cautionary tales, and personal accounts of brushes with the spiritual world. After each tale, the storyteller blows out a lantern.

One by one, guests take turns telling their eerie stories; recounting bizarre, strange and supernatural occurrences; reciting urban legends, myths, cautionary tales, and personal accounts of brushes with the spiritual world. After each tale, the storyteller blows out a lantern.

The lanterns form a circle around the room, and in the center sits a small wooden table with a mirror on it. After a guest blows out a candle, they are to stare into the mirror for a few seconds and wait. In the corner of their eye a shadow moves, or does it? They quickly return to the other guests. Some say, with each extinguished lantern, the spirits are invited one step closer, and after the 100th lantern is blown out, something supernatural is expected to happen…

No one knows when or where Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai (a gathering of 100 strange stories) originated, but it is documented as far back as the mid-1600s and is believed to have been played long before that. One of the earliest records of the game is by Ogita Ansei in his work titled OtogiMonogatari (“Nursery Tales”). According to Ogita, the game was first played by Samurai as a test of courage. He recounts a tale of a group of Samurai who went to a nearby cave and lit 100 candles. They each took turns telling a scary tale, and when finished, extinguished a candle. As the night went on, with each story, the cave became darker. The storytellers believed that without the light they would be vulnerable to the supernatural. After the last tale was told, the final storyteller went to extinguish the flame of the one remaining candle, when suddenly a large, grotesque hand appeared from the ceiling. Some of the Samurai cowered in fear until one brave warrior drew his sword and struck at the hand, revealing it to be nothing more than the shadow of a spider. The Samurai who cowered were mocked and ridiculed.

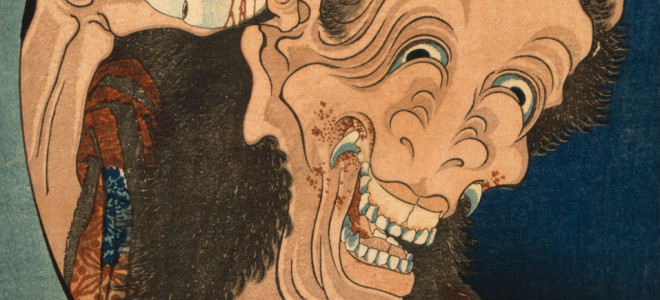

Originally a game for the aristocratic warrior class, Hyakumonogatari quickly made its way down to the working classes and became popular all over Japan. The game enjoyed the height of its popularity in the late Edo era (early 19th century) and in its heyday, Hyakumonogatari inspired people to scour Japan looking for new tales to shock and delight, leading to kaidan-shu (books designed to provide stories for the game) and many works of art by famed ukiyo-e (woodblock) artists such as Katsushika Hokusai.

How to Play the Game

• Get a group of at least three people together (The game is best played on the night of a full moon.).

• Prepare an L-shaped space consisting of at least two rooms, although three are preferable.

• In the center of the furthest room, place a mirror atop a table, and in a circle around it, light 100 candles or paper lanterns (made of blue paper instead of the traditional white paper). Blue lanterns are used as mood lighting as the blue color creates an eerie vibe.

• Participants should wear blue clothing (to match the lanterns and the vibe), and leave their swords at the door (Remember this game was devised in the 17th century; this was standard tea-house etiquette of the day. Modern-day participants should follow suit by handing over their guns, crossbows, mace, or whatever their weapon of choice, at the entryway.).

• Gather in the room furthest from the aoandon or candles and tell your stories. Traditionally kaidan were told, kai meaning “strange, mysterious, rare or bewitching apparition” and dan meaning “talk” or “recited narrative”. Kaidan are not the same as horror stories, and not exactly full-blown ghost stories, but just strange, unusual, or supernatural stories (The term is now used to classify a particular type of story of the traditional Edo era ghost tale.). But any spooky or hair-raising tale will do the trick.

• After a guest has finished their story they are to get up and go to the far room containing the lanterns and the mirror and extinguish one lantern. The person must gaze into the mirror before returning to the rest of the guests. It is believed that with each extinguished aoandon, as the room grows darker, yurei (japanese spirits) or yokai (Japanese monsters) are being drawn closer.

The Conjuring

• Once the hundredth lantern is blown out you are no longer protected from the spirit world and supposedly an unknown event will occur. Some say that once the spirits are summoned, supernatural occurrences can haunt participants uninterrupted for 30 days.

• Some believe it is Aoandon (who shares the name with the blue lanterns that became popular for the game) that will appear after the 100th lantern goes out. Aoandon is a female spirit dressed in a white kimono who has sharp teeth, long, black hair, and two horns sticking out of her head. Usually described as having a blue appearance or glow, she is the Japanese equivalent to Bloody Mary.

• If you’re eager to play the game, but not so eager to come face to face with horns, sharp teeth, or anything else supernatural, there is the option of simply stopping at 99 stories and leaving the last lantern burning. Many groups opt not to tell the last story, and instead spend the time chatting until sunrise.